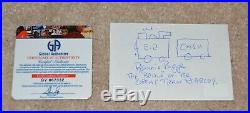

Ronnie Biggs Great Train Robbery 1963 Hand Signed Card With Message Drawing COA